Susan Engel

This blog is based on an article I co-authored with Deborah Mayersen, David Pedersen & Joakim Eidenfalk titled ‘The Impact of Gender on International Relations Simulations’ in the Journal of Political Science Education. While it focuses on teaching in politics, the issue of the impact of gender in the classroom more generally is just not discussed enough. Indeed, when starting out tertiary teaching, the text I was recommended on teaching hardly even mentions the terms women or gender and does not discuss the impact of gender on teaching.1 Yet classrooms are still very gendered spaces, even in the Humanities and Social Sciences where women are generally over 60 per cent of the classroom.

I was reviewing an article on the impact of gendered debate topics on simulations for the Journal of Political Science Education and the paper referenced work demonstrating quite gendered outcomes in high school Model United Nations (MUN) simulations, which grabbed my attention. MUNs are experiential learning simulations where participants role-play as model diplomats, discuss ideas and develop their own solutions to global challenges. We’ve been running one as a subject for a number of years now and previously analysed the impact on learning outcomes and our social media use but I had not really thought critically about the role of gender. I reflected that despite women being well over half of the class in our MUN, they probably spoke less than their share of the class. A review of the literature again demonstrated the limited interrogation of this question, so, we decided to do our own study on the impact of gender in simulations.

Our experiment investigated whether there was a gender disparity in student engagement in our MUN simulation conducted in a second-year undergraduate course in 2018 and, whether it could be reduced by introducing a deliberate gender-related training intervention. We had 117 second year students across five tutorial (or discussion) groups and around 65% of our students were women.

We undertook first, a gender intervention in three of the five classes focusing on the impact of gender in negotiation and second, examined the impact of gender in both the intervention and control groups by (a) recording student participation in the MUN by male and female participants, including speaking time and initiation of strategic actions; (b) undertaking an optional survey of student satisfaction and perceptions; and (c) examining student grades by sex.2

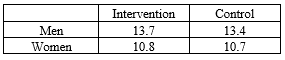

Table 1. Average speaking time per student in minutes by gender and group

The study found that, while there was variation across tutorials, women participated less than men, relative to their representation, and that this impacted their resulting grades, particularly in classes focusing on traditionally masculine topics. When adjusted for representation, female students spoke only about 79% of male student’s speaking time (see Table 1). Median grades for male and female students were very similar for the two written assessments, but in the simulation women scored notably lower. Further, the median grade for women in the intervention group was lower than for those in the control group. We posit that we inadvertently created a stereotype threat, that is, a situation where people perform worse in tests or other performance because of a stereotype about a group that they are part of. This has shown to impact even where people do not hold to the stereotype in question. In our case, it was around men being better at public speaking and women at supporting roles.

Chart 1. “Which MUN skills do you feel you excelled at most?” As a percentage of M/F respondents

The gender discrepancies continued in the survey, men and women perceived they excelled at different skills. As Chart 1 demonstrates, women were more likely to identify strengths in following MUN rules and procedures and writing resolutions, while men perceived they were better at public speaking and diplomatic skills. Women, particularly in the intervention groups, felt less confident as negotiators, less included in the simulation and enjoyed the subject less. Still, the vast majority of students felt that gender was not an issue in the simulation! The impact of gender and other diversity in the tertiary classroom is a topic in clear need of much more attention and research.

Susan is an Associate Professor in Politics and International Studies at the University the Wollongong. She lectures and researches in the areas of development, international politics and political economy. She has written one book and over 25 journal articles and chapters. Susan has volunteered with indigo foundation, a not-for-profit development NGO since 2002. Bio: https://scholars.uow.edu.au/display/susan_engel, twitter

@susanengel_oz

1In this case, John Biggs and Catherine Tang’s, Teaching for Quality Learning at University: What the Student Does (4th ed. Maidenhead: Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press, 2011), but there are others. There is also a lack of discussion around the impact of cultural and linguistic diversity in the classroom, which is a particularly profound issue for teaching in development studies.

2 None of the students in the class identified as LGBTQI+.